Venture Boldly

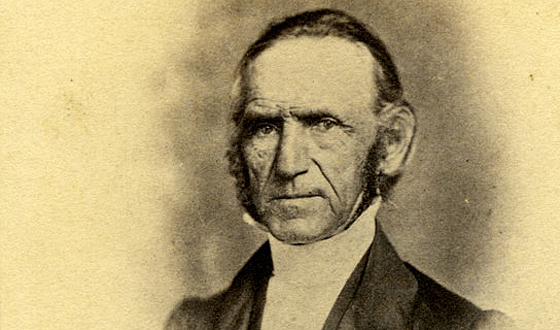

Pictured: Portrait of Knox College George Washington Gale.

The idea for Knox College originated in upstate New York in an area known as the ‘Burned Over District,' a reference to its prevalent evangelical revivals. Here, a group of Presbyterians and Congregationalists organized by the Reverend George Washington Gale formulated a plan for a religious manual labor college in the West. Their Circular and Plan, the blueprint for the foundation of Knox College, was significantly influenced by the religious environment that surrounded them.

George Washington Gale, founding father of Knox College, was born in Stanford, New York, in 1789. The youngest of nine siblings, Gale excelled in his studies and as a young adult traveled on horseback between rural New York towns, teaching in local schoolhouses. It was during these travels that Gale found religion in the homes of several of the families that boarded him. Gale set his sights on the ministry, and following his graduation with honors from Union College in 1814, he entered Princeton Theological Seminary, the leading Presbyterian seminary in the United States at the time. However, poor health due to dyspepsia (chronic and severe stomach indigestion) forced Gale to abandon his advanced studies at Princeton and pursue active missionary work instead. After a brief term of service in the Female Missionary Society, Gale received his ordination in the St. Laurence Presbytery, and settled down to preach in Adams County, in the Burned Over District.

Gale (undated sketch)

In 1824, Gale was again troubled by dyspepsia, this time leaving his pastorate to seek refuge in the warmer climate of the Southern U.S. coast. During his five months of travels, Gale had an opportunity to visit several colleges, including Georgetown, Hampton Sydney, and Thomas Jefferson's University of Virginia. The University of Virginia's secular nature especially intrigued Gale. He disapproved of founder Thomas Jefferson's decision to divorce religion from the university's operation, writing:

"It could not prosper on its present plan. It is among the appointments of God that literature and especially literary institutions cannot flourish except in conjunction with religion."

Although the vacation ultimately did little to mend Gale's health, it did have the effect of furthering his belief in the mutually beneficial combination of religion and education that would be the basis of his future endeavors.

Upon returning to New York in the spring of 1826, Gale relocated to nearby Whitesboro, New York, and began experimenting with schooling groups of young men on a "manual labor plan." Students who were eager for an education but unable to pay for the tuition were required to perform three-and-a-half hours of manual labor each day in exchange for remission on expenses for instruction, books, board, and lodging. The program was successful, evidencing its future viability as a systematic approach to higher education. Gale and other evangelicals saw other benefits in the manual labor philosophy as well. This form of education identified with the benevolence preached in the Burned Over District. It equalized opportunities for students of all backgrounds without the "evil of charity," and built upon the self-reliance and "health and bodily vigor" that was sometimes lost when students were dedicated exclusively to studies to the neglect of physical exercise. Thus it was that Gale saw the potential for manual labor, conjoined with religion, to "furnish the laborers" who would spread the gospel.

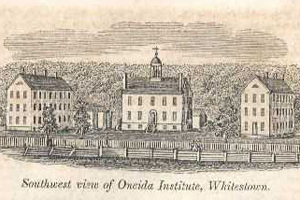

Oneida Institute

Gale's initial foray into manual labor in education precipitated the incorporation of the Oneida Institute in 1827, a manual labor training school for evangelists in Whitesboro County, New York. Gale described the enthusiasm with which he viewed Oneida and the manual labor enterprise in a letter to Charles Finney, describing it as an "impulse to a system of education that is to introduce the millennium," asserting that, "if you and I live 20 years longer, or half that, we shall see it." Gale directed Oneida Institute much the same as he had his educational arrangement with the group of students on his farm three years earlier: three hours of labor a day in exchange for room, board, and tuition. The institute opened to eight students in the fall of 1827, but by 1830 was turning away hundreds more due to infrastructural constraints. Gale's idea attracted considerable attention, not only from students but from patrons as well. Some of the most influential proponents of the benevolent movement contributed to Oneida, most significantly the nationally recognized entrepreneurs Arthur and Lewis Tappan.

Over time, the Oneida Institute developed a distinct abolitionist character that became a defining feature of the school. Many northern Presbyterians, Gale included, were stringent abolitionists on moral grounds, which manifested itself in Oneida's student culture. In 1833, students at Oneida founded an Anti-Slavery society, inspired by the rhetoric of William Lloyd Garrison. In written correspondences to the school's administration, the students relayed their impatience to spend more time at the college before entering regular missionary work and preaching the abolitionism they advocated. Abolitionism became characteristic of the Society for Promoting Manual Labor in Literary Institutions as well, which had the support of Arthur and Lewis Tappan as well. Many of the actors involved with Oneida volunteered with the Society as well, and collectively they helped guide the expansion of the manual labor system in the West during the 1830s and '40s.

Weld

Lane Theological Seminary in Cincinnati was one of the schools founded on the manual labor philosophy. Theodore Dwight Weld, a student of Gale's at Oneida, visited Lane in 1831 on behalf of the Tappan brothers and the Society for Promoting Manual Labor in Literary Institutions. He was charged with finding an institution in which the Tappan brothers and the Society might invest and promote, and he believed Lane to be the preeminent choice, both in terms of academics and from a religious standpoint. Weld wrote:

"Here is the great battlefield of the world, here Satan's seat is. A mighty effort must be made to dislodge him soon or the West is undone."

Weld, along with other discerning evangelicals, perceived the colonization of the West as a morally precarious enterprise. Young western cities were havens of moral decay, so they believed, and were constantly in need of a greater religious presence. The West was viewed as a moral salient, a battleground upon which the struggle for salvation would be waged from the pulpit, and in the classroom.

Oneida invested money and resources in Lane, not the least of which was its students. Lane Theological Seminary became a way point for students heading west. Weld influenced a number of Oneida students to transfer to Lane, which resulted in Lane developing an abolitionist character as well. Local reaction to abolitionism at Lane was much different than it had been at Oneida, however. Public opinion in Cincinnati derided abolitionism, and rather than the tacit acceptance they received in the Burned Over District, Lane students attracted that western city's ire through their advocacy of emancipation. In 1834 a riot was very nearly averted, probably only because of Lane's summer vacation. The Seminary's board of trustees, troubled by the acrimony between the city and the school, censored public displays of abolitionism and pressured Lane's students to disband the student's anti-slavery society. A great number of Lane students responded by leaving the school rather than returning and sacrificing their personal freedom. Instead, they founded Oberlin College the following year with the abolitionist principles they had been forced to forgo.

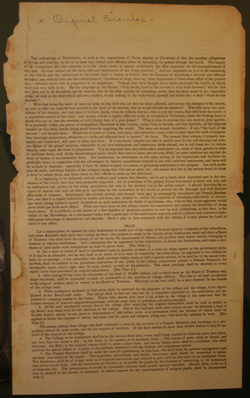

Knox's Circular and Plan

The expansion of the manual labor system contributed to George Washington Gale's interest in establishing a manual labor college in the west. In 1836, Gale released his "Circular and Plan," which formally defined his intentions behind the incorporation of a "Prairie College," as Knox was first known, and advertised the venture to potential subscribers. In his circular, he emphasized the use of manual labor as a tool to prepare students for pastoral work. Gale also stated his intent to open the college to women, which he would do with the construction of a Female Seminary in 1844. The progressive character of Knox College was thus derived from Gale's experiences as a preacher and educator in New York.

The subscribers, who became the Galesburg colony's first settlers, organized around Gale's philosophy and vision for the college as well. Many had been involved in Oneida in some form, and were, in general, supportive of the educational and religious mission espoused by Gale. These philosophies would characterize Knox College -- and Galesburg -- during the first decades of its existence through the College's involvement in the Underground Railroad and Anti-slavery politics. The idea behind Knox College did not develop on the prairie, but was rather born in the Burned Over District of New York.

Grant Forssberg '09

Blanchard, Jonathan. My Life Work, Presidents Series, Jonathan Blanchard, Biographies, Seymour Library Special Collections and Archives, Knox College, Galesburg, IL. Brown, Wyatt.

Lewis Tappan and the Evangelical War Against Slavery Cleveland: Case Western Reserve, 1969.Calkins, Ernest Elmo.

They Broke the Prairie New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1937

Dillon, Merton L. Elijah P. Lovejoy, Abolitionist Editor Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1961.

Gale, George Washington. The Autobiography of George Washington Gale, transcribed by Margaret Gale Hitchcock New York City: Not Listed, 1969.

Muelder, Hermann R. Fighters for Freedom: A History of Anti-Slavery Activities of Men and Women Associated with Knox College, New York: Columbia University Press, 1959

Muelder, Hermann. Missionaries and Muckrakers: The First Hundred Years of Knox College, Urbana, Chicago: University of Illinois.

Webster, Martha Farnham. Seventy Five Significant Years: The Story of Knox College, 1837-1912. Galesburg: Wagoner Printing Company, 1912