Venture Boldly

Office of Communications

2 East South Street

Galesburg, IL 61401

Working with a Knox College professor in a research project into secret codes in Japanese-American diplomatic history, a Knox student made a few surprising discoveries about herself and her own family history.

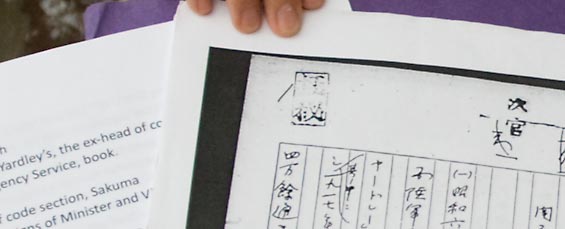

The professor is John Dooley, chair of Knox's computer science department, who has written extensively about secret codes in literature. The student is Yoshiko Kaimasu, a one-year exchange student from Waseda University in Tokyo. She has been assisting Dooley for several months by translating Japanese diplomatic communications from the 1920s. Photo above: Yoshiko Kaimasu discusses her translations with professor John Dooley.

Dooley is trying to determine whether Herbert Yardley, head of the U.S. Army's code-breaking unit during the 1920s, sold U.S. code-breaking secrets to Japan in 1930.

"Yardley headed the Army's first cryptanalysis unit -- involved in breaking codes -- during World War One," Dooley says "After the war, he convinced our government to continue a cryptanalysis bureau, and he was in charge of it through the 1920s."

"In 1967, there was a book, "The Broken Seal," about Pearl Harbor and the cryptanalysis failures that led up to Pearl Harbor, and the author, Ladislas Farago, accused Yardley of treason," Dooley says. "Farago wrote that in 1928, Yardley sold to the Japanese messages that he had decrypted and the methods that he had used. This accusation has now been repeated a dozen more times, but nobody has been able to find the exact Japanese government document that the author references."

"Was Yardley really a traitor?" Dooley asks. "All the books point back to one reference, one document, which nobody can find."

Will Trail of Evidence Prove a Traitor?

Hoping to track down the reference, Dooley went to the Gotlieb Archive Center at Boston University, which houses Farago's papers, and the U.S. National Archives, which has microfilms of thousands of Japanese government documents.

"In 1949, during the American occupation of Japan after World War Two, the U.S. microfilmed everything from the Japanese Foreign Ministry, and it's now in our National Archives," he says. Dooley was particularly interested a group of documents -- all in Japanese -- sent between Japanese diplomats in Tokyo and Washington between 1928 and 1932.

"Professor Dooley wanted someone to translate the Japanese documents," Kaimasu says. "He asked Professor [Ryohei] Matsuda [who teaches Japanese at Knox], who sent an e-mail message to some students at Knox, and a friend sent it to me."

"Professor Dooley wanted someone to translate the Japanese documents," Kaimasu says. "He asked Professor [Ryohei] Matsuda [who teaches Japanese at Knox], who sent an e-mail message to some students at Knox, and a friend sent it to me."

Coincidentally, Kaimasu is working toward a career in translation. "The project has helped me a lot," she says. "I had to translate about 300 pages from Japanese into English." The task was more challenging, Kaimasu says, because of the modernization in Japanese script in the past 60 years. "These documents are 'old' Japanese -- like Shakespearean English compared to English today."

In addition, some of the documents are harder to read because they were handwritten. But that also made the experience more personal, Kaimasu says. "When I see the handwriting, I think about the person who wrote it."

One day, Kaimasu says, she was talking on the telephone to her grandmother in Japan about the project, when she learned a surprising detail about her family history -- that her grandfather and Yardley were in the same business, at the same time, on opposite sides.

Spy vs Spy...

"My grandmother told me that my grandfather was a Japanese information officer. He translated [other countries'] documents into Japanese and was trying to figure out [other countries' diplomatic] codes," Kaimasu says. "Maybe my grandfather didn't work on any of these documents. But he worked for the Japanese Foreign Ministry, and he was trying to break American codes, so maybe he knew about the Americans [in Yardley's operation] who were trying to break Japanese codes."

"It's an amazing coincidence," Kaimasu says. "I never met my grandfather. My grandmother says 'You look like him. You are really like him.' We're both interested in language -- he knew English and German. After the war he worked as an officer of the American embassy in Japan and translated Japanese into English. I was so surprised that I'm doing the same thing that my grandfather did."

What Kaimasu did not find was the document that Dooley sought. "Yardley published a book in 1931, 'The American Black Chamber,' in which he discussed breaking the Japanese diplomatic codes. His book was a major embarrassment for the Japanese government," Dooley says. "Yoshiko translated one Japanese document that is dated ten days after Yardley's book is published on June 1, 1931. The Japanese Foreign Ministry knows that the Japanese Diet -- the legislature -- is going to start asking questions, and they're know they'll have to come up with answers for the Diet."

A Few Answers, Still More Questions

In its answer to the legislature, the Japanese Foreign Ministry admitted that it paid Yardley $7,000, but Dooley says it was apparently an attempt to keep Yardley from publishing 'The American Black Chamber.' "We found a document that accuses Yardley of being paid by Japan," Dooley says. "But the Japanese are saying: 'We paid [Yardley] $7,000 and he said he wasn't going to say anything, and what does he do? he says something'."

Dooley says his latest research has not settled the question. "Even if we didn't have these documents, we still wouldn't have any evidence that Yardley wasn't a traitor," he says. "But it reinforces the idea that there's no other documentation."

Dooley says his latest research has not settled the question. "Even if we didn't have these documents, we still wouldn't have any evidence that Yardley wasn't a traitor," he says. "But it reinforces the idea that there's no other documentation."

Yardley's operation came to an end in the late 1920s. "A law was passed that telegrams were private communication, so they couldn't get copies of telegrams from the telegraph companies," Dooley says. "And then in 1929, when Herbert Hoover was elected president, he appointed Henry Stimson as Secretary of State. When Stimson discovered that we were reading telegrams from other countries, including allies, he famously said 'Gentlemen do not read each other's mail.' "

Dooley plans to publish his results later this year.

A Knox Experience: More Languages, More Study Abroad

Wrapping up her work for Dooley, Kaimasu is turning her attention to another language, another country: "I'm taking Spanish 101Q," she says. The course is part of Knox's "Quick Start" program, in which beginning language students take an accelerated curriculum, culminating in a trip to a Spanish, German or French-speaking country. "Over spring break we to go to Guatemala. We will be staying in people's homes -- it's like studying abroad again."

"I have been studying English a long time," Kaimasu says. "In fall term I took Latin. It was difficult, but so interesting."

In June, Kaimasu will return to Waseda, where she is enrolled in its School of International Liberal Studies, SILS. She says she'll miss Knox's personalized environment, where faculty work directly with students on advanced research projects. "Waseda is a lot bigger -- 60,000 students. That's why I came to Knox -- because it's small. And every professor has so much knowledge."

Then there's the weather -- Galesburg is providing a stark contrast with Tokyo, where snow and cold don't hang around as long. "When I came here, I wanted to see snow," Kaimasu says. "Now it's still winter."

Published on February 26, 2010