Knox Stories

Michael Takeo Magruder Named First Knight Fund Distinguished Artist-in-Residence

Knox College will host its first-ever Knight Fund Distinguished Artist-in-Residence, Michael Takeo Magruder, from September 16 to September 30, 2025

Venture Boldly

Office of Communications

2 East South Street

Galesburg, IL 61401

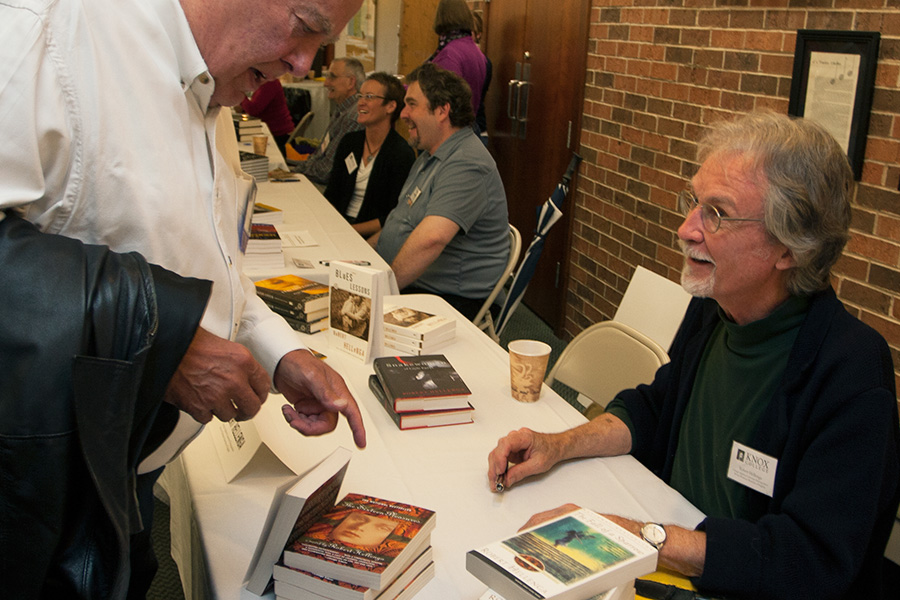

When Robert Hellenga, professor emeritus and distinguished writer-in-residence, started teaching at Knox in 1968, he thought that the world had enough worthy fiction and didn't feel compelled to create any more. But as he dabbled in writing, he fell in love with the craft and over the years transitioned from full-time professor to full-time writer.

This year marks the 20th anniversary of Hellenga's first novel, The Sixteen Pleasures. Rejected 39 times, the book went on to became a national bestseller and winner of the Society of Midland Authors Award for Fiction.

Hellenga has since written six other novels and garnered much recognition for his work, including a National Endowment for the Arts Artist's Fellowship.

Read an interview with Hellenga about the research that goes into writing a novel and his advice to aspiring writers, published in the fall 2014 issue of Knox Magazine.

Your novels include art conservators, avocado wholesalers, a painting elephant, snakehandlers -- how did you do your research?

I used to think that novelists just made everything up, but now I know better. For one thing, writers need to know what they're writing about; and for another, research almost inevitably leads to discoveries.

I started writing about Italy because we'd spent a year in Florence in 1982-83, and after that I started going back to Italy in order to write about it, and that's been the pattern ever since: back to Florence to write about making a film in Florence; to Bologna to write about the strage -- a terrorist bombing in 1980 -- in The Fall of a Sparrow; Texas to check out the avocado scene for Philosophy Made Simple; "Little Egypt" in Southern Illinois to check out the lay of the land for Snakewoman of Little Egypt; Rome to check out the Caravaggios for a novella.

I rely heavily on books too. I did not handle snakes for Snakewoman, but I did a lot of reading, especially oral histories -- autobiographies of snakehandlers -- and I managed to absorb the language of these snakehandlers.

I also talk to a lot of people: the vice president of the association of the families of the victims of the bombing of August 2, 1980, in Bologna, the janitor at the courtroom where the terrorists were tried, and the public prosecutor who tried the terrorists; a friend in Florence who helped sweep out the Cimabue chapel in Santa Croce after the flood and another friend who's restoring the ceiling of the apse in Santa Croce; and from the very beginning I've pestered Knox faculty members about all sorts of things, and I've relied on a neighbor for the low-down on the Shelby Cobra.

Of course the internet has changed everything. You can sit at your computer and find out just about anything you want to know. I use the internet all the time, but it feels like cheating.

What advice do you find yourself giving your students?

It's very important, I think, to discover things in the act of writing. If you're discovering things in the act of writing, then your readers will also discover things. By "things" I mean interesting generalizations that aren't simply truisms, epiphanies that catch you off guard, insights that go beyond the obvious, realizations that take you to someplace new.

It's important to leave yourself open to surprises at every step of the way, even when you're revising your 10th or 15th draft.

What are you working on now?

I've recently finished what I think is my best short story, "A Christmas Letter" (Ploughshares, spring 2014); I'm working on other short stories, and on a novella. The market for novellas is limited, but I think I've got a great title: The Truth About Death. So we'll see what happens. I'm also working on another piece that may or may not turn out to be a novel.

Published on February 03, 2015