Venture Boldly

Office of Communications

2 East South Street

Galesburg, IL 61401

In the early evening of a promising night, on the Knox College soccer practice field next to the Science and Mathematics Center, college students are getting ready for an evening with the stars. The sky is clear, and the twinkling stars seem close enough to touch. The constellations are bright and even satellites zip by.

In the early evening of a promising night, on the Knox College soccer practice field next to the Science and Mathematics Center, college students are getting ready for an evening with the stars. The sky is clear, and the twinkling stars seem close enough to touch. The constellations are bright and even satellites zip by.

It is an astronomy class observation night, and the majority of this class' observations are made by a few very active and enthusiastic observers. The group is lead by the astronomy class' teacher's assistant Andy Fitz '08. Most of the students are inexperienced observers, but a lot of practice and perseverance can turn them into well-trained amateurs, capable of understanding the night skies. On this clear night, they visually check their field of study hunting for familiar stars and planets.

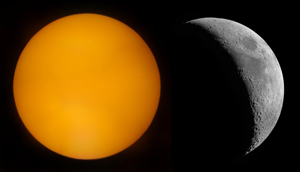

Fitz, a Physics and Secondary Education major, has also invited local students from Galesburg High School where he is observing a class before his student teaching term in the fall. Although they will view the moon, Saturn, Venus, Sirius and countless constellations, "Jupiter, which is really amazing to see, doesn't rise until midnight, and it reaches its peak about 2 a.m." Fitz says.

So there he sits, with computers on one side tracking the stars, plotting data in the sky and taking pictures. And, on the other side a large telescope points to the sky. The average night gazer might see a field of stars, but the skies the limit for Fitz who sees photons raining down and ricocheting off the polka dots that are light years away.

Star struck

In addition to his interest in Physics, Fitz is president of the Knox Photography Club, Photo Editor of The Knox Student, and he runs his own website, www.andyfitz.com. He seriously pursued photography after he took a black and white photography class in high school. Soon after, Fitz bought his first camera and by the next year, he was teaching other photography students how to use the darkroom. Currently, Fitz contributes photographs for many Knox publications, calendars, as well as the Knox College website.

It seems it was written in the stars. Fitz reckoned he could use his talents in photography along with his time spent with his astronomy classes to experiment with physics and photography. "Knox is a place where you can do that, do what you want; if you have the drive to make something happen, you can go ahead and do it, and the support is there from students and faculty to back you up," he says.

With his roommate and fellow physics major and photography enthusiast Charlie Brown, Fitz compiled an astrophysics project. "Our plan is to use digital photography to track the moons of Jupiter over time, measuring how long it takes them to orbit as well as how far they are from the planet. If we can get this data, we'll be able to calculate the mass of Jupiter. It's going to be a pain though, as there is a lot of light pollution in the area, the quality of the photos is not spectacular, and observations can only happen late at night."

In their calculations, Fitz and Brown mimick what astronomers have done in the past to find the masses of the planets. "The technique employs Newton's version of Kepler's Third Law. In terms of stars, the mass is what your really want, because from there, along with a few other fairly simple observations, you can extract a lot of information about that star."

As sunset fades on the soccer field Fitz readies the eight inch computer guided telescope and goes through the ritual of aligning the telescope so that it can track celestial bodies automatically. "The global positioning system built into the telescope is really nice. If you can get it to work, you can be up and running in about 20 minutes. It's nice because the telescope will find and track objects for you so you can keep them centered in the eyepiece," he says.

Most star gazers can not predict what they will see. That is the entertainment of what the average observer enjoys. Others, like Fitz and Brown, are attracted by the scientific value of their observations. "Astronomers gather data on the mass of a star, how much energy it gives off, and, through spectroscopy, what elements are present in its atmosphere. In my astrophysics class, we ask 'What can we extract from all this data? Why are there some stars that are so big that if they switched places with our Sun, they would go out to the orbit of Jupiter? Why are other stars only a fraction of the size of our Sun?' That's the fun part about astrophysics, really understanding the physics behind the phenomena," Fitz says.

The universe keeps getting bigger, and Fitz is quickly learning that there is more to the universe than anyone thought. The night sky is more than just a vast collection of stars. Astronomers discover black holes; find planets orbiting stars, and find stars 100 times more massive than our own Sun. We look nearby with more detail and far away with more clarity and we find some answers, but we always find far more questions. "How big is the universe? What's causing it to expand? What started the Big Bang?" Fitz wonders. "The answers to questions are like the Holy Grail of astrophysics."

Published on April 28, 2007